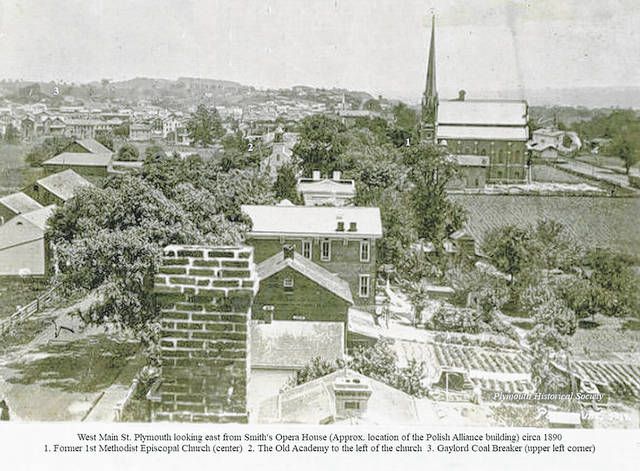

This is a photograph of the area described by Albert Young in his journal. The photographer of this 1890 photo is unknown. However, it shows a view of Plymouth, as seen from the upper floor of Smith’s Opera House. The opera house was approximately located at the site of the Polish Alliance Building. Recognizable structures in the photo are; the 1st Methodist Episcopal Church, in the center right. Today it’s used by Riot Circus Arts — the yellow painted building on Main Street, across from Downing Street; the old Academy is the white church like building with the steeple to the left of the Methodist Church. It was located at the corner of West Main and Academy streets; the Gaylord Coal Breaker is seen in the upper left corner.

Photo courtesy of Plymouth Historical Society

Journal from 1880s offers glimpse of Plymouth’s past

Click here to subscribe today or Login.

PLYMOUTH — Did you know that Plymouth had 34 bars or taverns during the late 19th century?

How about during the same time there were 12 doctors and seven druggists to treat the borough’s residents?

Well you do know thanks the journal of Albert Young and the hard work of Peg Makos.

Makos, who grew up in Plymouth Township, found the journal, which covered the time from 1888 to 1899, at the Plymouth Historical Society and asked if she could take it home and transcibe it. But it wasn’t easy.

Penmanship was difficult to read, but Makos said she got used to it. However, it took her three months to input everything into her computer.

”I loved every minute of it,” Makos said of her work. “At first, it seemed very boring, but I realized he did this for 10 years and only missed one day. The more I got into it, a pattern started. It was like I was reading a novel — a man’s diary — his journal.”

And now Young’s journal provides a valuable glimpse into life in Plymouth in the late 19th century, even if at first glance it seems the journal is nothing more than a daily weather report, a listing of all who visited his shop and notes of his “tinkering” in the shop everyday.

Makos began working on it at the beginning of the pandemic — she was at home and had time to devote to it.

“In the 1850 census, Albert was 2 years old,” she said. “And I discovered that his family lived in the house I grew up in at 1008 West Main St. But we had no family connection.”

Makos said the vast number of people who spent time with Young every day attests to how much he was revered by his peers and loved by his friends.

It might be noted that several Plymouth streets now bear the names of these friends — among then Davenport, Shupp, Wagner, Templeton, Turner, Duffy and Clark.

Makos said although Young referred to his daily activities as “tinkering,” this tinkering produced many fine and useful items for the residents of Plymouth, as well as more ambitious projects such as building boats, wagons, stables and barns. He even made peg legs for those in need. He was also an accomplished blacksmith and did work for the nearby Bowden stables, among others.

Makos said Young’s daily report of the weather may at first seem odd until taking into account that it was a common practice at the time. Prior to 1870 meteorological observations were done at military stations and the U.S. Weather Bureau was not created until October 1890.

Since Plymouth was situated along the Susquehanna River it was vital that weather records be kept not just for the farmers, but also for the many occupations dependent on the river. Rainfall, snow melt, high and low water levels were always observed and recorded.

At the beginning of the journal Young had just turned 41. His father, Charles E. Young, a steamboat captain, had died at age 71 in 1874. He was a very successful man and upon his death he left all his property and assets to his wife, Frances, and his middle son, Albert. Albert lived with and took care of his mother until her death at age 77 in 1900. He never married.

What follows is a transcriber’s notes and summary of the 1888-1899 daily journal of Young.

The Young Family

Charles E. Young 1803- 1874

Frances Gabriel Young 1822- 1900

Oscar R. Young 1839- ?

Susan E. Garrahan 1841- 1924

Emma Hutchison 1843- 1894

Mary G. Lowe 1845- 1926

Albert R. Young 1847- 1905

John Clayton Young 1849- 1928 (Clate)

Henrietta Frances Young 1852- 1931

Lazarus Young 1861- 1918

‘Prominent’ family

The Young family was very prominent and highly respected in the community. The men were members of various lodges and organizations such as the Knights of Pythias, the Masons, the fire company, etc., as well as being active in the community at large.

The eldest, Oscar, a blacksmith, left home in 1863 to fight in the Civil War. After mustering out, he married and moved to Indiana.

Albert speaks of Sister Em, who married and moved “out west” to Iowa. She came home to visit once.

The others married and stayed in Plymouth. Clate was an outside foreman at No.12 breaker for 42 years. He lived on Beade Street until he moved to Wapwallopen where he spent the last few years of his life.

Perhaps the most prominent was Laz, who owned and operated the L.R.Young Dry Goods & Grocery Store with his wife, Polly. The store began at the family home at 450 W.Main St. near Wadhams Creek. Laz lived at 154 W.Main St. near the present day post office. Albert had his shop in the rear. Together they built the larger, more permanent general store at 353 W.Main St.

Albert began his journal while living at 154, but when Laz built a new home on Turner Street, Albert moved back home with his mother at 450 West Main St., where he continued and completed the journal. His shop was then adjacent to that house. The barns and stables were in the back near the present day Hometown Market.

Plymouth way back then

At the time the journal was begun in 1888 the population of Plymouth was less than 9,000. By the end of the journal ten years later it was 13,000. Main Street was a dirt road. Albert frequently mentions the road being dusty in summer and being watered down to control the dust. The naphtha street lamps were ignited by lamp lighters, but only on nights when there was no moonlight. The incandescent light bulb was in it’s infancy. Gas lamps were used in the homes. On one summer night in 1892 Albert records that he and Laz went uptown to go through an electric light house which was on display.

In the first few years of the journal, Albert speaks of going for a ride every night after a day’s work either by himself, or with friends. He rode his horse or used a horse and buggy and always detailed the route that was taken.

On Sundays he took his mother, Laz, Polly and his friend Ange for a longer ride, usually up Harvey’s Creek road, or crossing the river by ferry and traveling up to Wilkes-Barre and back. They would stop along the way for a wintergreen or they would just enjoy the scenery. In winter they used a horse-drawn sleigh. Albert had several different horses. He spoke of trading and/or buying horses as we speak of trading and/or buying cars today.

Time on the river

Albert also spent a lot of time on the river. He details the days when the steamboats were running, or when they were stopped because of ice in winter.

In the spring of 1889 he and Laz bought a used ark for $15 and he rebuilt it. He also built boats for himself and for friends. By the end of summer, 1895 he spoke less of horses and more of boats and the river. His health and the economy were the determining factors. Days were spent boating and fishing rather than riding.

Milestone events

Throughout the journal Albert recorded events that helped shape Plymouth. He spoke of the terrible explosion on Feb. 25, 1889, at the Powell Squib Factory.

In August, 1890 he goes into great detail describing the cyclone that struck the area. He and his mother took rides to see all the destruction that it caused — houses moved, orchards destroyed, etc.

In 1891, he tells about riding up to watch them dismantle the Wilkes-Barre (Market Street) Bridge. He described them taking off the roof and sides so they could build a new iron bridge.

He recorded other milestones for Plymouth too, such as the 1892 building of a street railway beginning nearby at Coal and Main streets. Brick was also laid on the street beginning in 1892.

In May of 1899, No.2 Hose House was begun across from Albert’s house. At that time there were three fire companies in Plymouth and they were kept very busy. Not only were there numerous house fires, but there were also several mine fires, such as the Washington fan house in 1890 and the No. 8 breaker fire in 1894.

He details the 1892 fire of Old Sam Masters’ store and shop and the 1894 fire at William Weir’s storehouse in town.

It seemed that each year had its share of fires.

On Christmas Day 1894, a fire began in Yeager’s store and spread throughout Smith’s Opera House which was located at 132-134 West Main near Albert’s shop. The Opera House then moved to 410 West Main where it suffered another fire in 1896. Albert spent a good deal of spare time at the opera house store in both locations although he never spoke of attending any performances.

Finally, near the end of the journal Albert details a fire in September 1898, which started nearby at Wilcox’s stable and spread to one of the Young’s barns. Thereafter many days were spent on repair of both the barn and a nearby stable.

12 doctors, 7 druggists

At the writing of the journal, Plymouth had at least 12 doctors and 7 druggists to serve the residents. The typhoid epidemic of 1885 had just passed, but typhoid was still a problem.

In 1898, Albert lost Will Mapes, one of his dearest friends and helpers, to the disease. Antibiotics and vaccines were yet to be developed.

In May 1894, Albert did receive a vaccination that made him sick and unable to work for a few days. It was likely a smallpox vaccine since that was the only one available at the time.

For the first four years of the journal, Albert seemed to be robust and in fairly good health. Then on March 4, 1893, he fell very ill and was diagnosed with the grippe (influenza). He spent a week in bed. At that same time the weather became much warmer and the recent heavy snow covering began to thaw. The fast rising river soon began to flood his shop.

Although he was still sick, he and his friends managed to quickly move the contents of the shop as well as rescue and move the horses from the stables. Then he suffered a relapse and was too sick to leave his house for the next two months. He slowly got back to work but needed a doctor a few more times for lung pain and pleurisy.

Two years later he had another bout with the grippe that left him severely ill for four months. During that time he had five teeth pulled and also suffered with a lame back. Sick since January, he wasn’t able to get back to his usual work until September. Despite being so sick, he never missed an entry in his journal. Friends came to see him and helped to take care of him every day and night. After that, he often mentions that he is sick, but never stopped trying to work.

Other hazards

Aside from illness, there were other hazards mentioned in the journal. The mines caused many accidents. When there were lost limbs, Albert was able to help by making artificial legs. His friend, Billy Duffy, was fitted with one. He names others who came from outside Plymouth to have a leg made too.

The railroad that ran behind the house also caused some tragic accidents. In November 1892, his friend, D.P. Hendershot was killed by lumber falling from a train car. It was a slow, painful death, as there was no way to save him.

Regardless of the difficulties of life at the time, there are many accounts of happy times. Every work day was followed by an evening of rest and enjoyment. The men often gathered at the shop to play quoits until dusk. Then they would go inside to play dominoes and checkers.

It was also an usual occurrence for the men to meet out front by the store and just talk until bed time. The ladies did the housework. Albert boasts about his mother being able to do all her own housework at age 75 although he helps with the wash and sometimes helps clean.

More fishing

By 1895 fishing is mentioned more often. Even the wives of his friends and his sisters go fishing and put nets down in the river.

A boat ride every day was common. The usual route was across the river and up to Solomon’s Creek. There they would gather birch, walnuts and elderberries. In summer, they would go there for melons.

The island near there was also a favorite place to do target shooting. They did this often. Even the women participated.

Boating was a favorite past time in spring and summer, but in winter it was ice skating. Albert sharpened many pairs of skates every year. He made notes of the depth of the ice every day in winter. When it was thick enough they all went skating on the river. The ice was also cut and hauled to the mines when it was thick enough.

Another gathering place was Garrison Park, which he says was below the Washington Breaker. He would go to the Flats to watch the horses being bathed. In September 1894, he talks about horses racing at the Driving, or racing, park. All the best horses in Plymouth were there.

Plymouth parades

Plymouth also loved parades. Decoration Day was celebrated every year with a big parade made up of all the organizations in town. It went up to the Shawnee Cemetery where services were held and was followed by a picnic. Albert took his mother every year.

Columbus Day and Labor Day were also cause for a parade. In 1892, Albert describes a Labor Day celebration that included boat races among various Plymouth clubs and organizations. There were six steamboats filled with people and an estimated crowd of about 4,000 on both sides of the river.

That same year there was a 400-year celebration of Columbus Day. The mines were idle and shops were closed. Wilkes- Barre and all the surrounding towns, including Plymouth, held massive celebrations. Albert described Plymouth’s parade as being six miles long. According to the newspapers of the day, he was not exaggerating.

Perhaps the most curious was his mention of a “moneymen” parade held on Oct. 26, 1896. It was a huge parade that included brass bands, floats and speakers related to the upcoming election in November.

Holidays celebrated

As for holidays, Albert always mentioned Decoration Day, July 4th, Labor Day, Washington’s birthday and Columbus Day. He also mentions Coon’s Day (Groundhog Day) and Dewey Day (May 1, 1899, the day Admiral Dewey defeated the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay).

Although the Young family belonged to the Plymouth Christian Church, Albert only refers to church once when his mother sprained her ankle on her way to service that day. Christmas is only mentioned in 1891 when he gave his mother a Bible and Laz gave him some cigars.

34 saloons!

Due in large part to the mining population, there were at least 34 saloons in Plymouth when Albert wrote this journal. He never mentioned being inside any of them, and he even went to a Temperance meeting uptown in August 1892.

However, he made his own beer and cider and was very experienced at making both grape and elderberry wine for his family and friends. He made many trips to gather the berries every year.

In July 1889, he details an overnight trip that he, Laz, Polly and two friends and their wives took to gather berries on the mountain. It was a strenuous trip with the horses and wagons, but they harvested enough berries to make plenty of jam and wine.

In his spare time Albert was also busy making other supplies for the home. When his friend butchered his hogs, Albert used the fat to make soap and candles. He also made charcoal to burn at the shop and the stove in the house, and he even made the ink that he used to write his journal.

He made sauerkraut for the winter and when he caught fish in his nets, he shared with everyone.

He hated being idle as there was always something to do.

One of his favorite things was his orguinette. He mentioned it several times throughout the journal. It was a small instrument operated by a bellows and consisted of a cylinder similar to a player piano roll. When friends gathered, he would play it and he took it with him when he visited friends at their homes. By 1898 Edison had invented the gramophone and Laz purchased a talking machine. It was the forerunner to the phonograph. Laz would bring it to the house and everyone listened to it with delight.

Tone of journal changes

There was a noticeable change in the tone of this journal from 1888 to 1899. It reflected what was happening in the country as a whole. Until 1893 the country had been on a bimetallic standard, silver/gold. A drop in gold reserves sent the economy into a depression which lasted till 1894.

In 1894, Grover Cleveland was elected president. In 1895, there was a second recession followed by the Panic of 1896. This refers back to the October “moneymen” parade that Albert described. The Democratic/Populist party candidate, William Jennings Bryan, was running on the silver platform, and there were many visits to this area by members of the party trying to keep the bimetallic standard.

Parades, bands, speeches etc. were held to try to sway the voters. However, William McKinley was elected in November 1896, thereby securing the gold standard. He successfully steered the country out of the depression, but the GNP didn’t return to its 1892 level until 1899. During those years, Albert recorded how the people of Plymouth were suffering and struggling.

In 1895, he talked about the mines working only a few hours a week. In April 1897, he talked about times being very hard. Thousands of men were idle, there was no work and no money. Everything was cheap, but still no one could buy anything.

He listed prices of some articles — a good horse could be bought for $50, potatoes were 20 cents a bushel, eggs 10 cents a dozen, etc.

At the same time, the Nottingham and Avondale mines were flooded with water from the spring floods. Times were indeed very hard and Albert’s business suffered too. He had little call for work except for an occasional small job. He made some wooden swings, repaired some wagons and did some blacksmith work making hammers and filing saws.

He spent much of his time on the river setting nets for fish, target shooting and berry picking. He often hired friends to help him around the house and the shop. He had them do odd jobs such as painting the fence, trimming the grape vines, hauling ashes, anything to help them out.

In June 1898, an old friend, Wilson Conner, visited him from the west. He was excited to make a trade with Wilson. He gave him his muzzle loading rifle, two swords and a three-pound revolver for a camera that he valued at $20. He spoke of that camera and the fun he had with it until the end of his journal.

He and his dear friend, Harry Nungesser and Harry’s wife Mame would spend many days boating and taking pictures with that camera, and people often stopped in his shop to get their picture taken.

That summer they enjoyed their time listening to the talking machine, drinking elderberry wine and eating melons that they frequently bought at 8 for 25 cents. By late 1899, work began to pick up a little and Albert was getting more jobs to do, although things were still quite slow.

That winter was extremely cold. In February, the mines had to shut down because of heavy snows and bitter cold. An ice jam in March was followed by a flood bringing two feet of water under the shop. And Albert was sick yet again.

Albert Young was certainly a well-loved man. He was rarely alone. His brothers, sisters and friends were always around and he was always there for them.

The journal ends in August 1899. In the entire decade, only one entry was left blank. Albert’s mother died the following year and Albert died five years later.

Except for brother Oscar in Indiana and sister Em in Iowa, the entire Young family and their children are buried in the Shawnee Cemetery.

Reach Bill O’Boyle at 570-991-6118 or on Twitter @TLBillOBoyle.